Former News of the World man defends brutal Sunday tabloid world

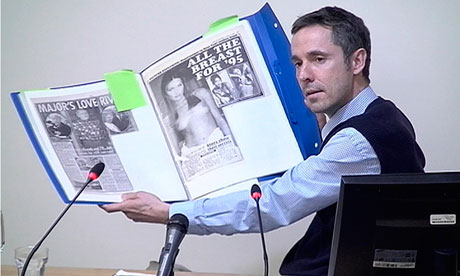

Former News of the World journalist Paul McMullan takes the witness box with his cuttings book at the Leveson inquiry. ‘Circulation defines the public interest,’ he said. Photograph: Reuters

'Privacy is for paedos," declared former News of the World man and tabloid veteran Paul McMullan in the midst of his evidence at the Leveson inquiry. He had only just observed that "in 21 years of invading people's privacy I've never found anybody doing any good" – statements that together amounted to a credo for the brutal Sunday tabloid world of which McMullan became the chief spokesman in the otherwise stifled confines of courtroom 73.

Which, he argued, apparently gave cause for a culture of blagging, surveillance, and even phone hacking, although he stopped short of incriminating himself on that one.

In some moments, it was impossible not to admire the bravery and the brio, as McMullan's career flashed before our eyes. He was sent home from the Gulf war – because it was not interesting Screws readers – and gave up investigative journalism after a lump of concrete was thrown at his head when he was looking into asylum seekers at Sangatte. But he "absolutely loved giving chase to celebrities.

Before Diana died it was such good fun. How many jobs can you have car chases in? It was great." And you could almost believe it, before he made the suggestion that Sienna Miller should be "cockahoop" because she had 15 photographers outside her house harassing her, because "who's she?"

McMullan paid one "rent boy" £2,000, then dressed up as another to expose a priest. Having snapped the picture of the reverend in flagrante, the two ran off in their underpants "through a nunnery at midnight" to get the story safely into the paper. "That under Piers Morgan," McMullan said.

Leveson seemed largely content to let this all play out, but it often seemed a bit too graphic for David Barr, the lawyer for the inquiry who nominally had the task of drawing out McMullan through his questions. In fact, Barr battled to hold the man back; at one point he tried to dissuade McMullan from holding up a cutting of one his proudest stories – a topless shot of Carla Bruni. McMullan did so anyway.

It should perhaps have not come as a surprise that McMullan would defend the decision to hack into Milly Dowler's phone, which "was not a bad thing for a well-meaning journalist who is only trying to find the girl to do". One can only wonder what the Dowler family think of that.

As he arrived at the high court, McMullan asked an ITV journalist for the way in. He was advised that if he chose the side entrance he would be filmed and photographed. The side entrance was the route he chose.

McMullan wanted his viewpoint to be seen and heard; after all, he said, he felt that Rupert Murdoch "didn't have a right to close" the News of the World where people like him swam and survived.

But if there was grandstanding, it was still worth hearing every word: here espoused was the end point of the regulation-free, market-driven, anything-goes tabloid morality.

And for it, he was paid £60,000 a year as deputy features editor, and claimed £15,000 to £20,000 in expenses, of which, he added, "£3,000 was legitimate".